The amount of employee data that organizations collect is exploding with the digitization of work and with novel digital connections with employees such as workforce wearables (e.g., smart watch, wearable panic button) and mobile devices. We suspect few leaders appreciate the diversity and volume of data about employees that their organizations are amassing. Just during the recent pandemic, employee data has expanded to include vaccination cards and frequent health checks, virtual meeting behaviors, and work-life surveys.

At most large global firms, people and workforce analytics are mainstream initiatives led by HR leaders. But increasingly employee data is being used beyond HR, and it is being combined in new ways. In recent MIT CISR research, we studied dozens of AI projects, many of which included employee data.[foot]In 2019–2020, MIT CISR researchers conducted 100 interviews with participants of 52 distinct AI projects at 48 firms. In 2021, the authors reviewed 22 of the projects that demonstrated significant use of employee data and analyzed them using the lens of the CARE framework.[/foot] For example, one initiative analyzed deidentified employee badge use, affiliated business unit, Wi-Fi device connection activity, and building characteristics to generate insights about building occupancy, and saved the organization millions of dollars in reduced heating and cooling costs.

Innovative uses of employee data, however, can surface uncomfortable insights. Particularly in digital transformation contexts, employee behaviors and knowledge are key to understanding how an organization has historically operated. This understanding can expose opportunities for improvement, and lead to unanticipated outcomes when the organization decides to radically alter or eradicate work tasks moving forward. Such uses of the data can cause tensions and be fraught with gnarly ethical concerns.

Organizations may be tempted to govern employee data by relying on guidance from regulations such as GDPR and HIPAA, which are rooted in personal data privacy and protection. But these laws fall short when it comes to ethical oversight of employee data use. For one thing, employees present with ethical complexity due to the employer-employee relationship and because of their embeddedness in firm operations. Also, MIT CISR research has shown that a regulatory-based perspective is not broad or deep enough to comprehensively oversee the internal and external use of people data; firms need a capability known as Acceptable Data Use (ADU) that includes legal, regulatory, and ethical oversight practices.[foot]B. H. Wixom and M. L. Markus, “To Develop Acceptable Data Use, Build Company Norms,” MIT Sloan CISR Research Briefing, Vol. XVII, No. 4, April 2017, https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/2017_0401_AcceptableDataUse_WixomMarkus.[/foot] ADU also covers values-based oversight, which incorporates the expectations and desires of the organization and key stakeholders such as customers, donors, and suppliers.

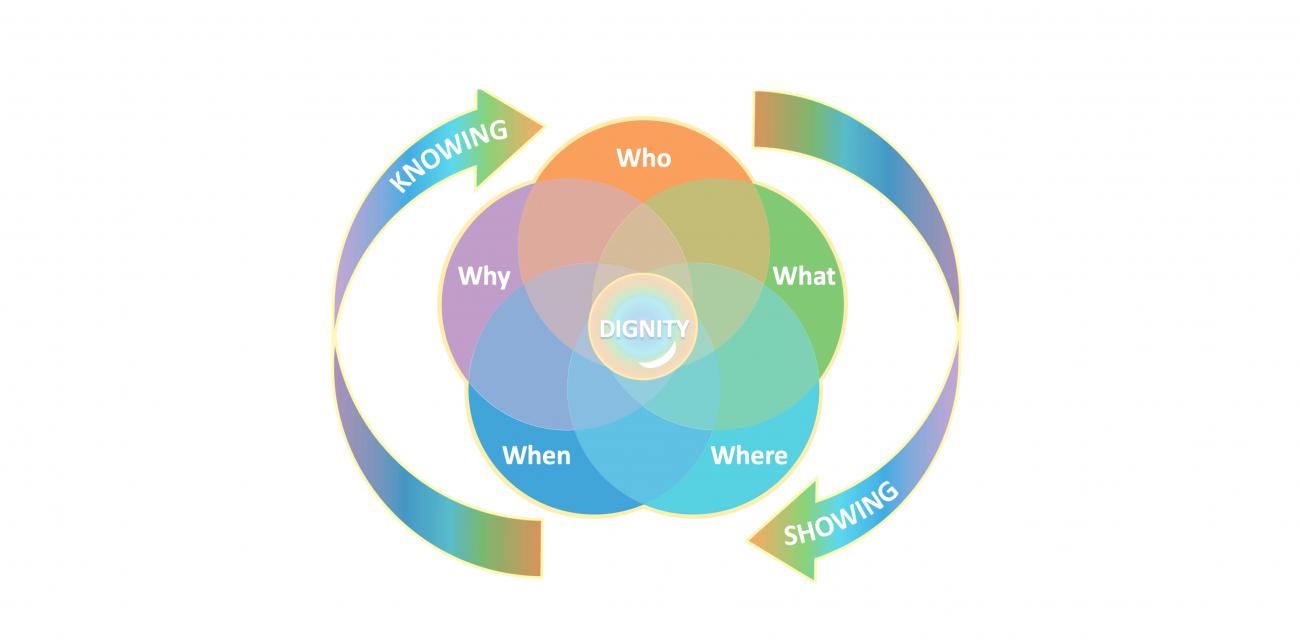

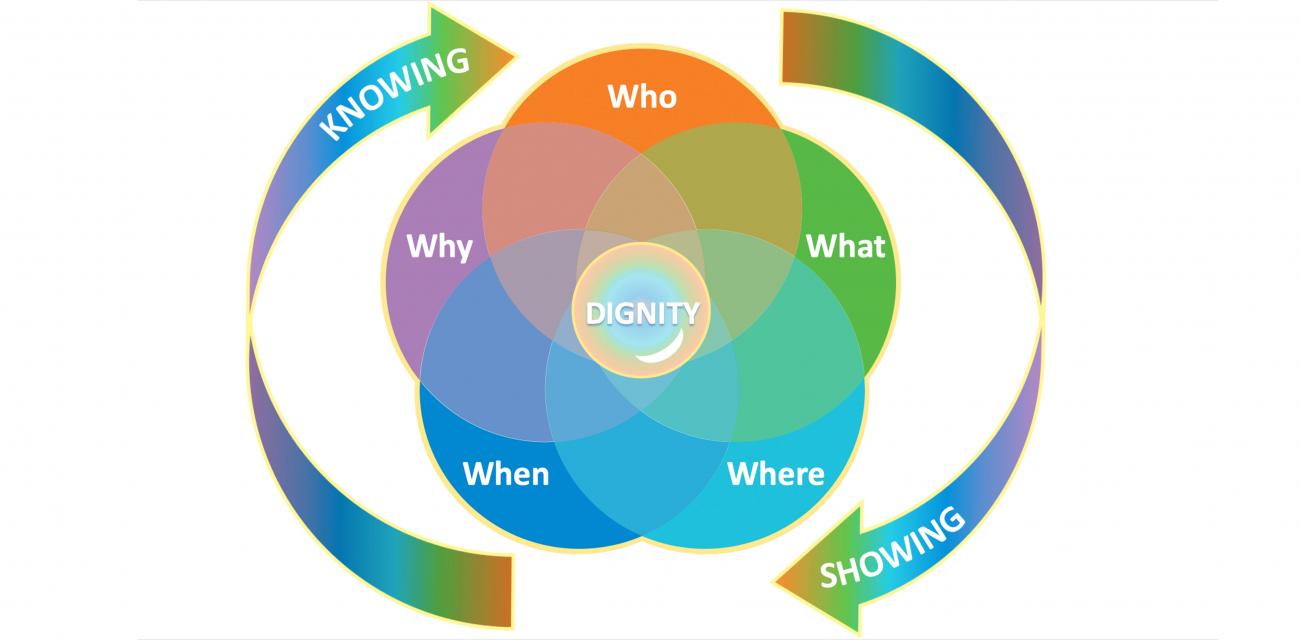

An academic article published this year by the first two authors of this briefing suggests that leaders can effectively manage ADU-associated ethical and values-based requirements of employee data use by focusing on dignity.[foot]Dorothy E. Leidner and Olgerta Tona, “The CARE Theory of Dignity and Personal Data Digitization,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 1b, January 15, 2021, https://misq.org/the-care-theory-of-dignity-and-personal-data-digitalization.html.[/foot] In fact, we believe that putting dignity at the center of acceptable data use not only improves ADU management but also allows transformation leaders to reinforce the organization’s regard for its employees.