Identify Risks in Core GenAI Components

To make GenAI risks concrete, consider a specific example: a hiring manager using GenAI to draft a job description for a new role. What seems like a simple task—type a request, receive a polished draft—involves multiple components, each introducing distinct risks.

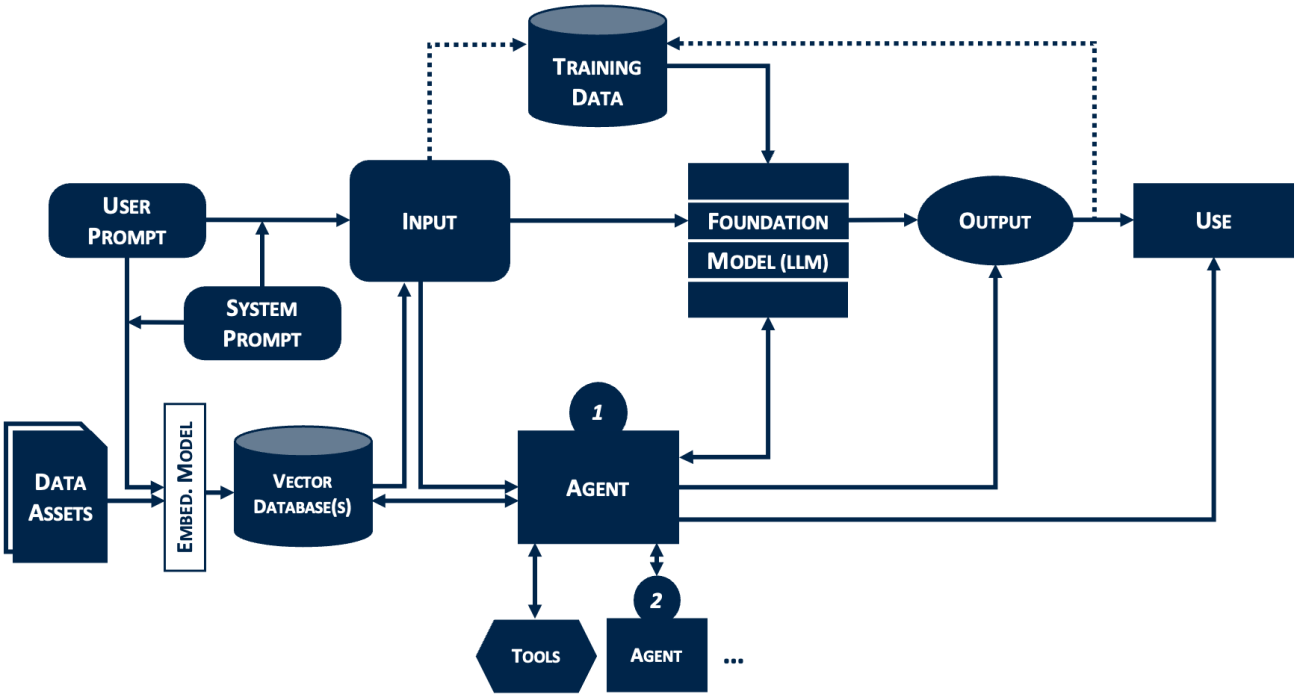

Training data: Foundation models have been trained on massive datasets, primarily scraped from across the internet. For our hiring manager, this means the model has absorbed millions of job descriptions and résumés, but also outdated HR practices, biased language, and inaccuracies. As such, the risk is that the model can confidently generate requirements that are incorrect for the hiring manager’s industry or region, or that the output reflects outdated norms rather than current best practices. The organization doesn’t control the training data; it inherits whatever the model’s developer used.

Foundation model: The foundation model (typically a large language model, or LLM) distills training data into patterns it uses to generate responses. These models are inherently probabilistic, meaning that if the hiring manager provides the exact same input to the model multiple times they’ll obtain different outputs each time. Foundation models also run the risk of generating “hallucinations”: plausible-sounding content that is factually wrong. And because the reasoning inside these models is opaque, organizations can’t determine why a particular output was generated—which makes such errors difficult to diagnose and correct.

Models also change significantly as vendors push updates, sometimes without adequate notice. One executive described the challenge of keeping pace: “[Model provider] employees are not allowed to present a deck to a customer if it is more than 48 hours old... Because [the provider is] moving so fast, the information in that deck is no longer current.” The risk is thus that what works today may fail after an update.

User prompt: For GenAI tools to be effective, users must know how to properly direct (“prompt”) the model. The hiring manager needs to provide the right context for the job description, as well as clear instructions and examples of what a good job description looks like. Without clear direction, the model’s output likely won’t meet expectations.

Users can also introduce risks unknowingly. When using public GenAI tools, users may inadvertently disclose sensitive information by including confidential data, proprietary strategies, or personally identifiable information in prompts. Or the user could fall victim to prompt injection, where malicious content hidden in documents or websites manipulates the model’s behavior. For our hiring manager, copying text from a compromised template could inject instructions that cause the model to leak information or act against their intent.

System prompt: Enterprise-grade GenAI tools and solutions typically combine user prompts with a hidden system prompt to enforce organizational context and constraints. This system prompt functions as the model’s “constitution,” setting tone, operational logic, and safety guardrails that supersede individual prompts. As system prompts govern every interaction, they require careful design and regular review. A poorly engineered system prompt creates a single point of failure that can lead to errors, security vulnerabilities, or hallucinations across the organization. A rigid, legally compliant system prompt could sanitize our hiring manager’s directions, for instance, resulting in a generic boilerplate job description that lacks the excitement needed to attract top candidates.

System prompts are also vulnerable to prompt leakage. Through clever questioning, users—or bad actors—can coax the model into revealing its hidden instructions. Once exposed, competitors can replicate proprietary logic, and attackers can craft inputs designed to circumvent the organization’s security guardrails.

Output: The model can generate a job description in seconds. It looks professional and appears authoritative—but it may contain biased language, inflated requirements, or fabricated qualifications. The polished appearance makes it harder for the hiring manager to spot errors. Yet proper evaluation of the output is essential, as the cost of errors can be significant. As one executive mentioned, “The probability of hallucination may be low, but the negative consequences of hallucination are really high for us.” That is why some organizations enforce this directly: “Do you have the expertise to challenge the output? If not, you’re not allowed to use GenAI.”

Use: Finally, the hiring manager decides what to do with the output. They might use the output as inspiration, edit the model-drafted description, or accept it wholesale and post it as presented. Errors that remain internal can be caught and corrected; errors that reach external stakeholders can damage trust and reputation. Qualified candidates may not apply if AI-generated requirements seem unrealistic, or they may recognize AI-generated content and question the organization’s judgment. The hiring manager’s decision to post without careful review could cost the organization the very talent it sought to attract.