CREATE A PORTFOLIO OF EXPERIMENTS

Evolving a digital value proposition involves funding many small experiments to maximize learning. Funding experiments isn’t hard. Companies encourage widespread experimentation through events like hackathons and other competitions, special funding opportunities like internal Kickstarter[foot]Kickstarter is a crowdfunding platform for launching creative projects; https://www.kickstarter.com/.[/foot] projects or a Shark Tank[foot]Shark Tank is an American reality television show on the ABC network in which aspiring entrepreneurs make business presentations to a panel of five “shark” investors; https://abc.go.com/shows/shark-tank.[/foot]-style proposal review process, and new organizational units like innovation labs and digital business units. The idea is to produce a pipeline of new ideas from many parts of the company, particularly from people who interact regularly with customers.

Of course, such widespread innovation could simply waste resources on pointless experiments. Companies can counter that risk by insisting on small experiments that quickly produce measurable outcomes. Any experiment that doesn’t quickly generate customer enthusiasm can be abandoned, while those with the most potential can be cultivated. Leaders can also articulate specific desirable business goals, in order to focus experiments on a set of outcomes that are important to them. Making it crystal clear what specific business outcomes leaders are seeking helps distinguish winners from losers, but most of all, it stimulates everyone’s thinking in the right direction.

It’s true that some major technological innovations will take time to develop. Autonomous driving capabilities fall into this category. Enhancing a vehicle with artificial intelligence involves long, sustained investments. But it’s worth noting that autonomous driving is a product enhancement. Automobile manufacturers that insert autonomous driving capabilities into their cars will rely on traditional strategies and traditional product development processes. This is not an experiment—it’s a big bet.

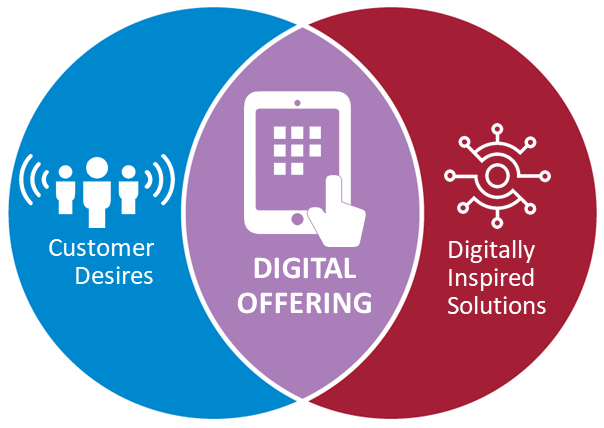

Digital offerings are different. They are solutions. This is why AUDI AG’s mobility solutions address people’s need to go somewhere, their desire to drive a great car, their hope that parking in big cities will become less of a hassle. To test how best to meet those needs, AUDI has created a separate digital innovation unit that engages in experiments exploring mobility solutions.[foot]Mocker and Fonstad, “How AUDI AG is Driving Toward the Sharing Economy.”[/foot]

Experiments at DBS Bank in Singapore are pervasive.[foot]Siew Kien Sia, Christina Soh, and Peter Weill, “How DBS Bank Pursued a Digital Business Strategy,” MIS Quarterly Executive 15, no. 2 (June 2016): 105-121, https://misqe.org/ojs2/index.php/misqe/article/view/529/.[/foot] In 2015, the company was concurrently running one thousand small experiments throughout the bank. DBS continues to encourage experiments through mechanisms such as internal crowdsourcing, customer experience labs, hackathons, external partnering, nurturing of FinTech startups, and technology scanning. Some of the experiments are quickly abandoned; others evolve into digital offerings or features for customers.

When DBS initiated its digital efforts in 2010, the company targeted first-class customer experience. As part of that effort, the company established multiple organizational units to teach most of its 22,000 people test-and-learn concepts, design thinking, and customer journey analysis. Subsequently, DBS started capturing data from sensors on customer touchpoints so that employees could analyze customer habits and needs. Leaders then articulated the specific desirable business goal of eliminating 100 million wasted customer hours, and empowered people to innovate to achieve that goal.[foot]K. Dery, I. M. Sebastian, and N. van der Meulen, “Building Business Value from the Digital Workplace,” MIT Sloan CISR Research Briefing, Vol. XVI, No. 9, September 2016, https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/2016_0901_DigitalWorkplaceBusinessValue_DerySebastianvanderMeulen.[/foot] Within a year, they had eliminated 250 million hours of customer wait time, while also cutting 1 million hours of wasted employee time.

DBS’s digital strategy has evolved as the company has learned from its experiments. In 2014 DBS was committed to making banking “invisible;” today, the company’s vision is making banking joyful, with the branding position “Live more, Bank less.[foot]“DBS signals time has come for new kind of banking,” DBS Newsroom, May 15, 2018, on the DBS website, https://www.dbs.com/hongkong/newsroom/DBS_signals_time_has_come_for_new_kind_of_banking.[/foot]” DBS’s digital strategy initially led to simple apps that enhanced the customer experience, but by 2016, the company had introduced an entirely digital bank in India. In 2017 and 2018 it began offering car, property, and electricity marketplaces on the DBS website.