Now that many business executives have embraced the idea that data is an asset, they are quite excited to monetize it. But what exactly is data monetization and how do organizations do it? MIT CISR research[foot]In Q1 2014, MIT CISR research scientists interviewed 58 executives at 34 companies regarding the companies' data monetization approaches.[/foot] discovered that definitions of data monetization vary widely: “selling data as a new revenue source,” “leveraging data in new ways,” “using data to make better decisions,” “placing a quantitative value on insights gleaned from data,” “understanding your customers so well that you can proactively make their lives better.” In fact, earlier this year we interviewed nearly sixty executives engaged in data monetization efforts—and extracted about sixty unique data monetization definitions from those conversations.

Cashing In on Your Data

Abstract

In a digital economy, data and the information it produces are among a company’s most important assets. Increasingly, companies are monetizing their data assets through selling, bartering, or wrapping (i.e., wrapping information around core products and services). This briefing describes these three approaches and reflects on the opportunities and risks associated with each. We also identify some of the competencies and practices that help firms “cash in” on their data.

To develop new and growing revenue streams, an increasing number of companies are selling information.

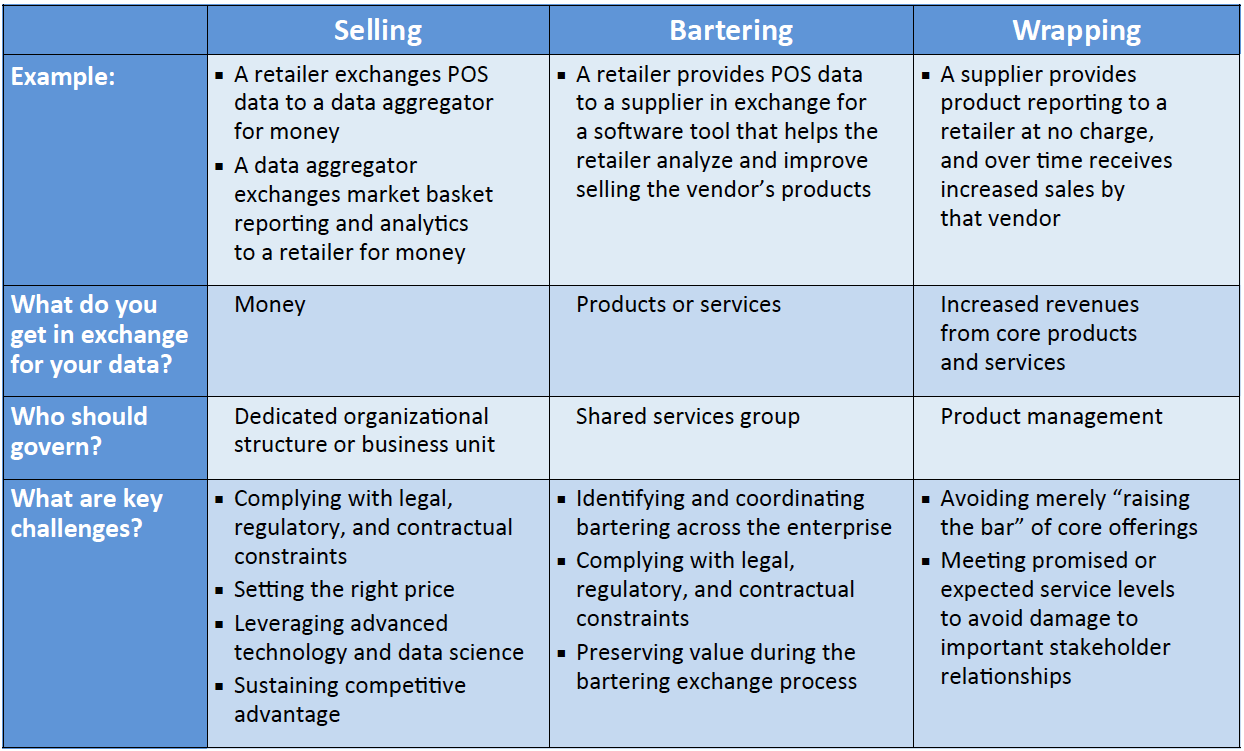

We define data monetization as the act of exchanging information-based products and services for legal tender or something of perceived equivalent value. Our research identified three approaches to data monetization: selling, bartering, and wrapping, which refers to wrapping information around core products and services. This briefing describes these three approaches and reflects on the opportunities and risks associated with each (see figure 1). We also identify some of the competencies and practices that help firms “cash in” on their data.

Selling Data and Information

Companies have been selling data for years. Consider the retail industry: for decades, retailers have sold point of sale (POS) transaction data to consumer research firms like Nielsen or dunnhumby, which in turn sold aggregated data and associated reporting and analytics back to retailers and other organizations that wanted to better understand product sales. POS data represents an important raw material to the aggregators, and thus can generate a substantial revenue stream for retailers. However, selling other kinds of retail data is not as straightforward. For example, significantly fewer retailers sell customer data from their loyalty programs because privacy concerns and contractual obligations more than offset the allure of incremental revenues.

To develop new and growing revenue streams, an increasing number of companies are selling information, from reports and analytics to self-service portals, consulting services, and business process outsourcing. Opportunities for information-based offerings are so lucrative that they have given rise to contemporary information companies like comScore.[foot]comScore is an analytics company in the digital advertising space. See B.H. Wixom, J.W. Ross, and C.M. Beath, “comScore, Inc.: Making Analytics Count,” MIT Sloan CISR Working Paper No. 392, November 2013, https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/MIT_CISRwp392_comScore_WixomRossBeath.[/foot] They have also inspired new businesses within existing companies, such as Mercy’s[foot]Mercy is the fifth largest Catholic health care system in the US. See www.mercy.net.[/foot] foray into healthcare analytics. Owens & Minor, a medical supplies distributor, offers a useful example of a company that seized the opportunity to leverage its core data to sell information products and services.

Selling Information at Owens & Minor

In 1997, Owens & Minor[foot]D. Stoller, B. Wixom, and H. Watson, “WISDOM Provides Competitive Advantage at Owens & Minor: Competing in the New Economy,” Society for Information Management (2000).[/foot] began selling reports and basic metrics on products and services it distributed from hundreds of suppliers to several thousand hospitals. For example, Owens & Minor would sell to hospitals reports that communicated how many and which products were bought off contract or drop shipped, i.e., through high-cost purchasing practices. These information products—now called spend analytics—were purchased by hospitals to make better decisions about procurement, and by suppliers to make better decisions about product distribution and market penetration.

Over time, Owens & Minor’s information offerings evolved from reporting and metrics to also include self-service portals and professional services, and then business process outsourcing, whereby the company would assume a hospital’s procurement process and own the ability for its performance. One reason for this evolution was that as customers grew savvier, they became hungrier for more sophisticated information products. A second reason was competition. Once Owens & Minor delivered a new information-based product or service to the marketplace, other distributors—along with group purchasing organizations, vendors, professional services firms, and pure-play analytics companies— were quick to copy or deploy similar offerings.

As this evolution occurred, Owens & Minor created a separate division called OM Solutions to focus on its information-based business. Top management recognized that OM Solutions required different capabilities such as advanced data and technology management. Also, OM Solutions’ margins were much higher than the slim margins associated with the Owens & Minor core distribution business. Business leaders chose to structurally separate the businesses so that each business model was managed appropriately. On several occasions, OM Solutions acquired or partnered with other firms to expand or build new capabilities. For example, it acquired Paragon Ventures for its data cleansing and contract digitization software in order to build master data management capabilities for product data.

Although data monetization may seem like a hot choice to generate top-line growth, it requires thoughtful consideration and due diligence.

Success Factors for Selling Data and Information

Selling data and selling information represent unique business models, and they require an organizational group or business unit dedicated to building the requisite technical and business competencies appropriate for the magnitude of the business. For companies that choose to sell data, the organizational group should contain superior vendor management capabilities, which ensure that transactions comply with legal, regulatory, and contractual obligations. The group also needs expertise in pricing. An insurance executive noted that capabilities like pricing can be very difficult for data-related businesses: “There is no marketplace to put data out there and learn the value of a ranking or rating or scoring. Can someone get the same data for free somewhere else? Or at better quality?”

Companies that intend to sell advanced information products and services must establish the competencies described above but require additional competencies in cutting-edge technology management and data science. comScore, for example, has extraordinary technology talent capable of leveraging open-source products or building home-grown solutions to produce highly efficient platforms often many times cheaper than mainstream alternatives. These solutions are exploited by people with varying levels of analytics skills across the organization.

Data and information sellers must also continuously evolve offerings to ensure that they remain valuable and rare. comScore constantly scans the environment for the next best thing through deep industry involvement and heavy customer interaction, and embraces agile approaches to quickly bring new ideas to the market.

Bartering Data

Bartering data is a less ambitious undertaking than the selling approaches to data monetization. Bartering can represent an appealing business proposition because companies can gain new tools, services, or special deals in exchange for their raw data. In the earlier example of retailers selling POS data to data aggregators, those same retailers could instead choose to exchange their raw data for information products and services such as reports, benchmark metrics, or analytics software over receiving money. Like selling data, however, companies must regularly assess whether the tender they receive justifies the expense or risk it entails. One healthcare executive warned, “We wrestle with [bartering]. We have concerns about losing control regarding what the data ultimately will be used for.” For some companies, the real concern about bartering is that individual business units may engage without recognizing the value of what they are giving up.

The keys to bartering are to identify where it is (or should be) happening and to ensure that the bartering process is formally managed. Ideally, a centralized process or organizational unit should be accountable for safeguarding data from being distributed, integrated, shared, and used in the future in ways that would risk the firm’s reputation. This governance mechanism should also ensure that the company does not give away value and complies with contractual, regulatory, and legal requirements. For example, one executive in our sample described how he had to turn down an offer for a “free” analytics service in exchange for its transaction data; although the traded data would be aggregated and anonymized, it still violated the company’s customer agreement.

Wrapping Information

In a recent poll,[foot]We surveyed sixty-three executives at MIT CISR Summer Session 2014 on the topic of data monetization.[/foot] 73% of executives chose wrapping as the data monetization approach that offers the greatest future potential for their companies. Wrapping occurs when companies generate bottom-line financial impact by packaging “free” information products and services with core offerings. The desired outcomes of wrapping include increased market share, wallet share, switching costs, and prices. UPS executives declared years ago that the information about a package was as valuable as the package; the company has been enhancing customer information services ever since. Several B2B companies in our sample wrap billing analytics around core products to help their business customers analyze spend; they all described this service as an important value-add for their business customers. An executive from an insurance company described how his firm supported brokers with information that would enable them to better offer the firm’s insurance products: “We are very explicit in not charging for that information. We do it as a way for our representatives to enhance their relationship with the broker.”

To succeed in wrapping, companies must deeply understand their markets and partnerships— and what information offerings their users value—and incorporate wrapping into core product and business capability roadmaps. As companies invest in wrapping activities, we offer one caution: the benefits of wrapping information products and services around core offerings may be short lived and does pose the risk of simply raising the bar for customer expectations.

Companies that choose to wrap information around core offerings must deliver at high service levels. If wrapped information is not delivered with the same quality standards as core offerings, then it poses a reputational risk to the customer/stakeholder relationship. Data management and technical best practices help build industrial-strength capabilities to ensure that information products are ready for delivery outside of the firm. For example, master data management and virtualization or cloud can help beef up competencies in data standardization and scalability, respectively.

How Will Your Company Cash In on Data Monetization?

In past decades, most companies generated business value from data internally by analyzing operating processes and customer demands and then identifying opportunities to improve and innovate. Today with data monetization, larger numbers of companies want to generate business value from data externally by selling, bartering, or wrapping. This ups the data game. Thus, although data monetization may seem like a hot choice to generate top-line growth, it actually requires thoughtful consideration and due diligence, regardless of the data monetization approach you select. To cash in on data monetization, be sure you have committed the necessary resources.

Figure 1: Three Data Monetization Choices

© 2014 MIT Sloan CISR, Wixom. CISR Research Briefings are published monthly to update MIT CISR patrons and sponsors on current research projects.

About the Author

MIT CENTER FOR INFORMATION SYSTEMS RESEARCH (CISR)

Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT's tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our research is funded by member organizations that support our work and participate in our consortium.