To ensure their long-term competitiveness, most large organizations are augmenting their investments in digital innovation. For example, they are increasing the number of digital innovation efforts launched, agile teams, hackathons, and partnerships with start-ups.[foot]A digital innovation is a new (for the organization) or significantly improved offering or capability that relies on digital technologies. A digital innovation effort is an investment of resources over time intended to generate business value through innovation.[/foot] Yet these investments are merely inputs to realizing a company’s digital ambitions. By only focusing on such inputs, leaders can lose sight of the outcomes of the company’s digital innovation investments.

In fact, many innovation efforts generate outputs of little or no value. They end up producing “fondue sets”—innovations that intuitively seem worth developing, but once developed, are rarely used, difficult to improve, and end up generating little if any business value. Tracking inputs helps to kick-start innovation efforts, but it doesn’t ensure accumulated learning about how those efforts contribute to business outcomes. And without such insights, executives struggle to prioritize and adapt efforts, and consequently, to generate value from them.[foot]Read more on learning from hypotheses in J. R. Ross and N. O. Fonstad, “Learn from Hypotheses, Not Failures,” MIT Sloan CISR Research Briefing, Vol. XIX, No. 5, May 2019, https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/2019_0501_LearningFast_RossFonstad.[/foot]

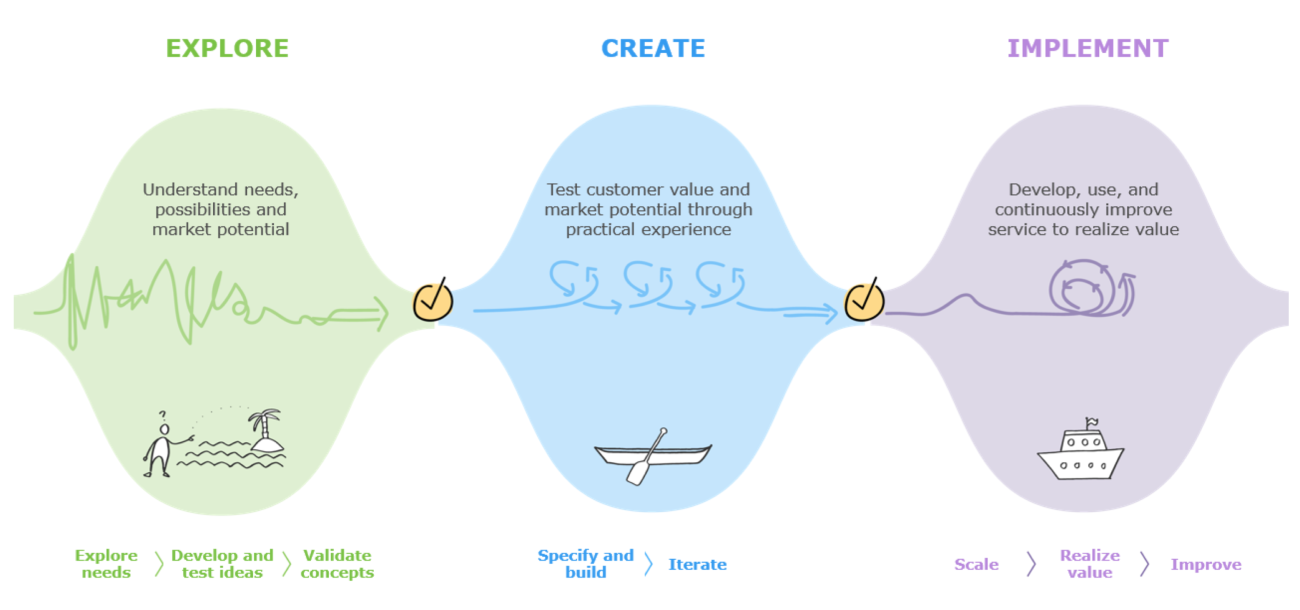

I have studied twelve organizations that successfully changed their approach to innovation and no longer create fondue sets.[foot]I performed interviews with over thirty executives at twelve firms from 2017 to 2019, conducted as part of the research I led on Expanding Digital Innovation.[/foot] These organizations refocused their approach from increasing inputs to increasing the value realized from individual innovation efforts. They changed the desired outcomes of an innovation effort to generating insights into what makes an offering desirable, feasible, and profitable—and why—and developing a digital offering based on those insights. And they changed decision rights, making cross-functional teams responsible for realizing these outcomes.

Posten Norge AS, hereinafter referred to as Norway Post, is an example of a company that has shifted the focus of its digital innovation efforts from inputs to outcomes.[foot]For our full case study on Norway Post, see N. O. Fonstad, “Innovating with Greater Impact at Posten Norge,” MIT Sloan CISR Working Paper, No. 440, January 2020, https://cisr.mit.edu/publication/MIT_CISRwp440_InnovationPostenNorge_Fonstad.[/foot]