Effectively doing business in emerging markets is a key issue for organizations: developing countries are among the fastest-growing economic regions in the world. But emerging markets are characterized by volatility and ambiguity as well as considerable uncertainty. They are very different from the mature, developed, industrialized markets that are more familiar to most corporations. As a result, trying to do business in ways that succeeded in developed markets is unlikely to work well.

Digital Innovation in Emerging Markets: A Case Study of Mobile Money

Abstract

Developing countries are among the fastest-growing economic regions in the world, but they involve considerable volatility and uncertainty. In this briefing, we examine the opportunities and challenges of doing business in emerging markets through the case of Vodafone’s M-PESA mobile money system. We describe how this digital innovation evolved into a highly successful financial service in the Kenyan marketplace, but struggled to achieve similar rapid growth and impact in neighboring Tanzania. Contrasting these two experiences, we argue that a strategy of exploration is more effective than one of replication for leveraging digital innovations in emerging markets.

Kenya's M-PESA system is the most successful mobile service in the world.

Using the case of Vodafone’s M-PESA system, this briefing examines the opportunities and challenges of doing business in emerging markets. We describe the success of M-PESA in Kenya and the subsequent disappointment when M-PESA was replicated in Tanzania. We show how emerging markets are likely to be more different from than similar to one another. Thus, companies should consider a strategy of exploration as they attempt to expand within emerging markets.

Vodafone’s M‐PESA

UK-based Vodafone Group is the world’s second-largest mobile telecommunications company (2013 ROA of 13.2% compared to an industry average of 5.0%).[foot]Financial information from www.reuters.com[/foot] In 2005, Vodafone built a small-scale digital innovation for Kenya—the M-PESA mobile money system (“M” for mobile, and “PESA” for money in Swahili)—that facilitated the transfer of money by mobile phone without a bank account. This application is particularly powerful in a country like Kenya, where some 90% of the population is unbanked. After early difficulties and subsequent learning, Vodafone revised and repurposed this limited innovation, developing in the process the most successful mobile money service in the world, and one that everyone is trying to emulate.

M-PESA was initially developed by Vodafone as a mobile-based, microfinancing application funded partially by the UK Department for International Development to extend financial access to the unbanked populations in East Africa. Managed by the corporate social responsibility (CSR) group within Vodafone, M-PESA was designed for a niche market: microfinancing institutions and their clients. The project was intended to be low-cost, low-key, small in scale, and modest in scope—focused on addressing issues of financial inclusion within the developing world.

Vodafone’s CSR group partnered with Sagentia, a boutique technology development firm in the UK, to develop the application. Developers piloted the application in Kenya with the local mobile provider Safaricom. After running the pilot for a few months, the project team found that rather than facilitating microloan disbursements and repayments, the application was being used for general money transfers by the clients. The team realized there was an opportunity to develop an alternative, broad-ranging money transfer system, and Sagentia and Vodafone consequently modified the initial application to enable electronic deposits, payments, and withdrawals of money via mobile phones.

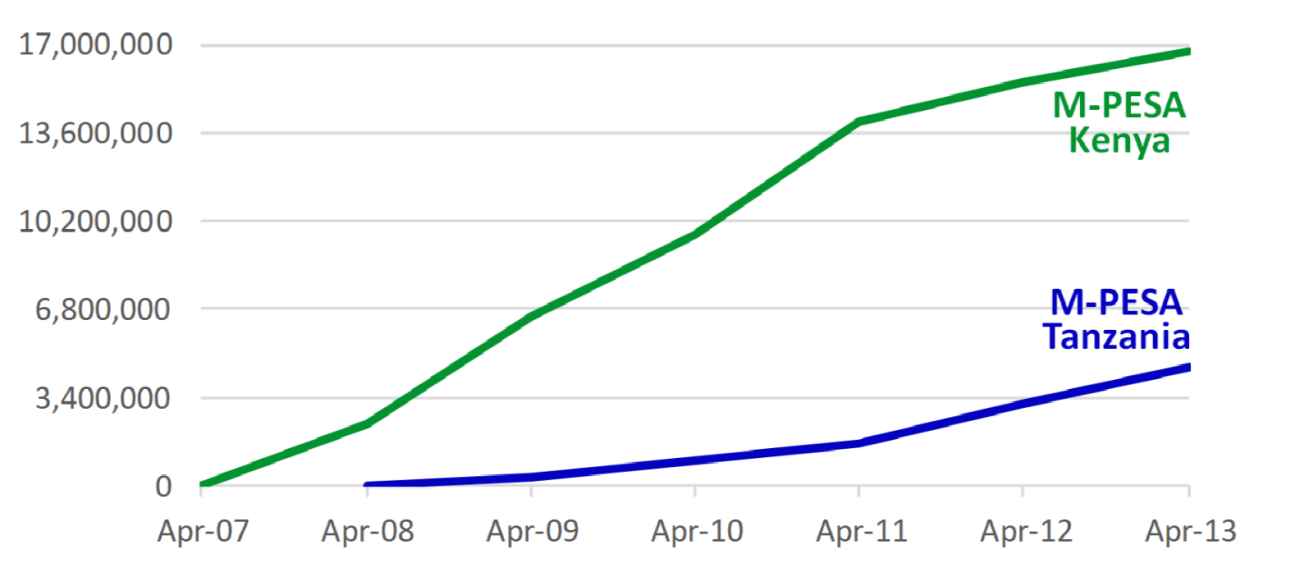

The redesigned M-PESA system launched in Kenya in April 2007, growing rapidly through uptake and user innovation of new services. Now used by over 17 million Kenyans—which is more than two-thirds of the adult population—it is estimated that annually some 31% of the country’s GDP flows through it.[foot]Harvey Koh, Nidhi Hegde, and Ashish Karamachandi, Beyond the Pioneer, April 2014, https://www.fsg.org/publications/beyond-pioneer[/foot]

In 2008, a year after launching in Kenya, Vodafone attempted to replicate this success in neighboring Tanzania, a country that resembled Kenya in many important ways—size of population (40+ million) and main languages spoken (Swahili and English), as well as levels of literacy, unbanked, and mobile phone usage. But M-PESA in Tanzania did not grow on anything like the scale and scope of M-PESA in Kenya (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Growth of M‐PESA in Kenya and Tanzania

Different strategies toward the digital innovation resulted in different innovation practices and outcomes.

Neighboring Emerging Markets: So Close Yet So Far

Our analysis revealed three reasons why the Tanzanian deployment failed to generate the results accomplished in Kenya.

- Consumer Need

Kenya had a long tradition of rural to urban migration, with members of a household moving to the cities to work and regularly sending money back to their families. Most Kenyans do not have a bank account, so money was traditionally carried home by traveling back to the rural areas, a costly and risky means of moving money. Consequently, there was a crucial need for a safe, secure, and reliable mechanism for transferring money over large distances. M-PESA filled this void. It was launched with a clear and simple marketing campaign—“Send Money Home”—that resonated powerfully with a pressing consumer concern.

In Tanzania, the message of “send money home” did not resonate. In contrast to Kenya’s tradition of urban migration, Tanzania’s experiment with socialism followed a “villagization” policy that created far less rural migration to the large cities, and much less need to “send money home.” The compelling value proposition for a mobile money transfer system proved harder to identify and articulate.

- Infrastructure

Safaricom in Kenya was the biggest network provider (at 70% of market share in 2007) with a very large distributed network ready, available and able to start selling M-PESA services. Growth in the agent network has kept up with growth in usage of M-PESA—expanding from 350 to 28,000 retail outlets in four years. Current estimates have the number of M-PESA agents at over 40,000.

At launch of M-PESA within Tanzania, the local network provider—Vodacom—was not a major player, with only 41% of subscriber market share. It had a smaller infrastructure and a considerably lower number of agents (numbering some fifty retail outlets operated through five national retailers) who were largely concentrated in the cities.

- Regulatory Environment

Kenyan regulators were open to financial innovation because of the low level of bank penetration. As a result, they worked closely with Safari-com, learning from the early experiences of M-PESA and formalizing regulations later.[foot]Ignacio Mas and Daniel Radcliffe, “Mobile Payments Go Viral: M-PESA in Kenya.” In Punam Chuhan-Pole and Manka S. Angwafo (eds.), Yes Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent, The World Bank, 2011: pp. 353-369.[/foot] As one commentator put it, their policy was that “regulation should follow innovation.”

In Tanzania, the Central Bank was similarly interested in financial inclusion and approved the service without stringent regulations. However, it lacked a close relationship with the local mobile provider (Vodacom), and thus required more monitoring because of concerns about the risk of money laundering. Furthermore, in contrast to Kenya, Tanzania lacked a national ID system, which precluded the use of a readily available unique personal identifier for registering and authorizing M-PESA transactions. Signing on to and using the M-PESA service in Tanzania proved to be a cumbersome and time-consuming process.

While these important differences in local conditions help to explain some of the variation in M-PESA results, they reveal a more consequential underlying lesson: different strategies toward the digital innovation resulted in different innovation practices and outcomes in the two emerging markets.

Exploration vs. Replication Strategies in Emerging Markets

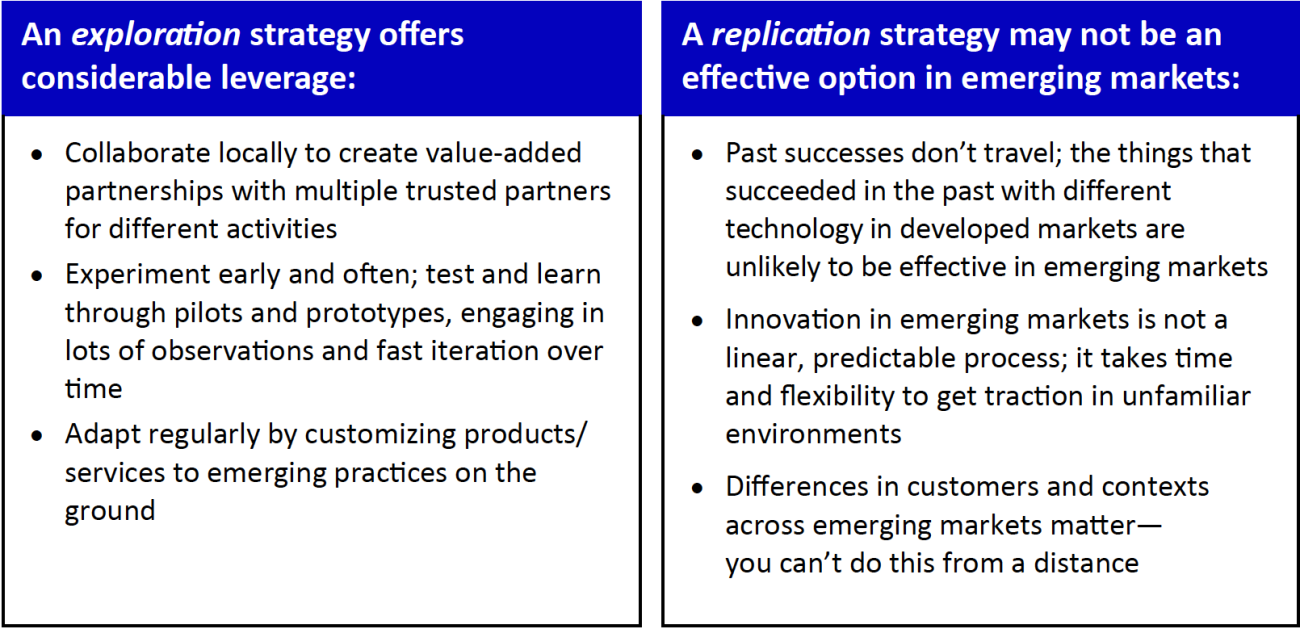

In Kenya, Vodafone followed a strategy of exploration (see figure 2 for a comparison of strategies). It ran pilots, partnered with local companies, and learned from what was working and what wasn’t. When it found that the initial concept did not work well on the ground in Kenya, it was willing and able to abandon initial assumptions and shift strategy. Vodafone’s collaboration with Sagentia and Safaricom allowed the development of a more general application and service infrastructure for the Kenyan context. Together these companies worked with the Central Bank to establish the reliability and security of the technology platform and they ensured that agents in the network were adequately trained and had in-store support, thus affording customers a consistent, dependable, and easy-to-use service experience throughout the country.

In Tanzania, Vodafone followed a strategy of replication. Rather than sending developers to Tanzania to run pilots and learn from practices in the field, it reasoned that the neighboring countries were similar on many levels, and having refined M-PESA over the past year in Kenya, decided to manage the implementation process from Europe. As a result, it did not realize that “sending money home” would not resonate with Tanzanian consumers; it was unable to recognize that the different size and concentration of the agent network within Tanzania would require different training and support; and it did not develop trusting or collaborative relations with the regulators. Choosing to reuse the Kenyan marketing and education materials, Vodafone failed to discover what might have become the indispensable "killer app" within this emerging market.

Summary

While markets in developed countries share many common features, markets in emerging countries often have more differences than similarities. In such conditions, a replication strategy may not be an effective option as it does not allow the experimentation, iteration, and adaptation needed for learning and leverage. Thus, while digital innovations offer a powerful opportunity for doing business in emerging markets, they require a strategy of exploration.

Figure 2: Two Different Strategies Toward Digital Innovation in Emerging Markets

© 2014 MIT Sloan CISR, Orlikowski and Barrett. CISR Research Briefings are published monthly to update MIT CISR patrons and sponsors on current research projects.

About the Authors

MIT CENTER FOR INFORMATION SYSTEMS RESEARCH (CISR)

Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT's tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our research is funded by member organizations that support our work and participate in our consortium.