Since the mid-1990s, companies have been implementing ERP and CRM systems, banking engines, consolidated customer files, and other technology infrastructure comprising their operational backbones.[foot]An operational backbone is the set of systems and processes that ensure the efficiency, scalability, reliability, quality, and predictability of a company’s core operations. See J.W. Ross, I.M. Sebastian, C.M. Beath, S. Scantlebury, M. Mocker, N.O. Fonstad, M. Kagan, K. Moloney, S.G. Krusell, and the Technology Advantage Practice of The Boston Consulting Group, “Designing Digital Organizations,” MIT Sloan CISR Working Paper No. 406, March 2016.[/foot] These efforts have helped companies dramatically enhance the efficiency and reliability of their core operations. But the features of the operational backbone did not address the growing demand for integrated digitized solutions and personalized, multichannel customer engagement.[foot]For one company’s recognition of the need for a digital services platform, see P. Andersen and J.W. Ross, “Transforming the LEGO Group for the Digital Economy,” MIT Sloan CISR Working Paper No. 407, March 2016.[/foot] That is why companies now need a second set of technology resources—what we refer to as a digital services platform. This briefing describes the purpose and features of a digital services platform and offers some early insights into how companies are designing governance to build and manage that platform.

Your Newest Governance Challenge: Protecting and Exploiting Your Digital Services

Abstract

Among the many opportunities from the digital economy, API development is leading to new electronic linkages within and across companies. These linkages facilitate efficiencies and new sources of revenue—but they are almost too easy to develop! MIT CISR research and the thesis research of an MIT master’s student has found that as companies become proficient at developing APIs, they should quickly architect a platform of digital services capabilities rather than just creating a growing number of one-off APIs. This briefing introduces some early governance considerations that could contribute to a robust platform.

A digital services platform is an organically growing set of components that constantly introduces new functionality. It helps companies capture the benefits of new technologies and new sources of data.

WHY COMPANIES NEED A DIGITAL SERVICES PLATFORM

A digital services platform does not replace an operational backbone. Rather, it complements it to enable rapid innovation. Born-digital companies like Amazon and Google have clearly demonstrated the benefits of a technology platform that facilitates connecting to reusable technical and business components. These companies accelerate innovation by making reusable business components available to developers—both internally and externally.

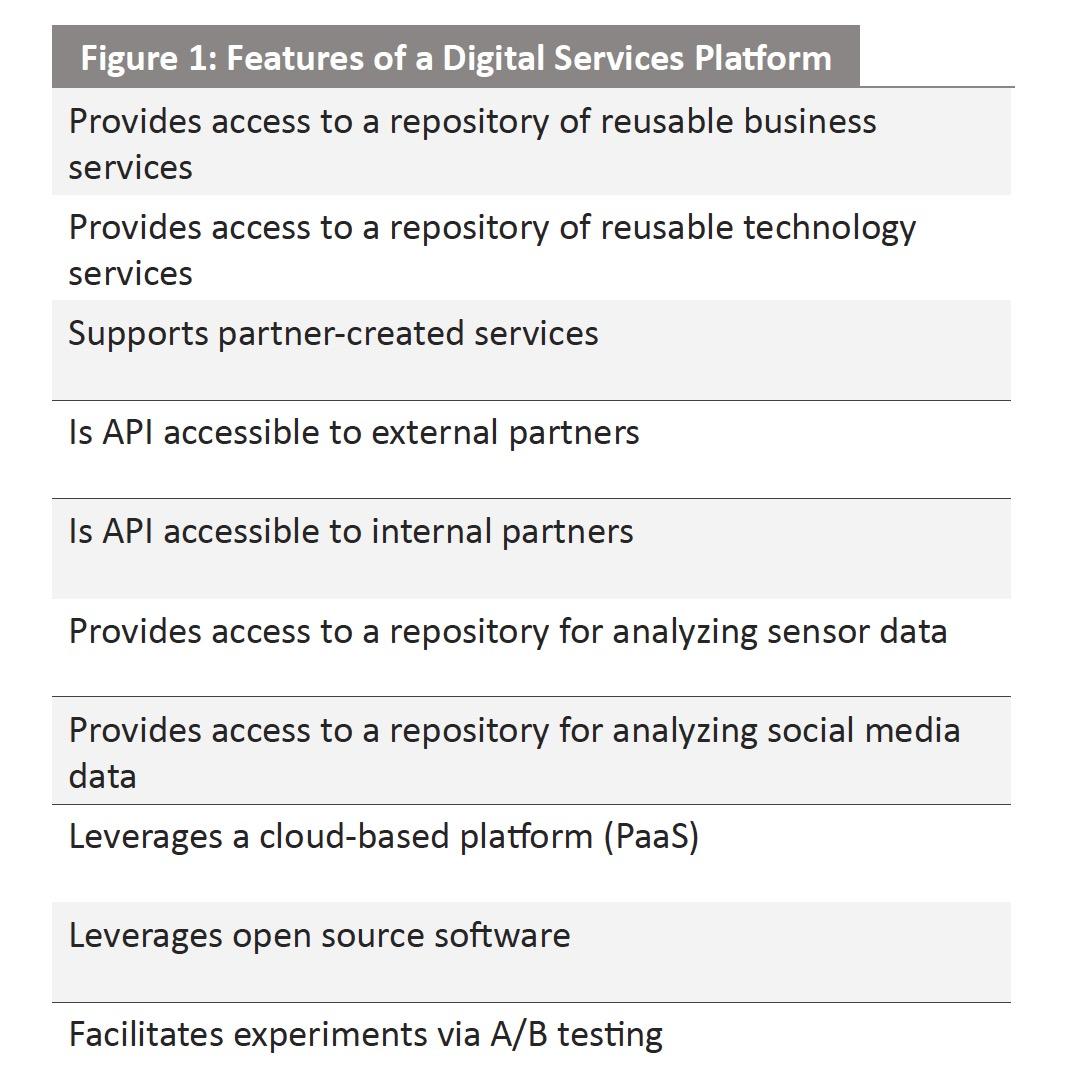

MIT CISR research has identified a set of ten key features common to a digital services platform (see figure 1). Together these features help companies capture the benefits of new technologies and new sources of data. In a recent survey of 171 senior executives, we learned that companies with a digital services platform were 3 times more innovative and 2.4 times more agile than companies without such a platform.[foot]The Designing Digital Organizations 2016 Survey, N=171, was conducted jointly by the MIT Sloan Center for Information Systems Research (CISR) and The Boston Consulting Group (BCG). More details will be available in J.W. Ross, I.M. Sebastian, C.M. Beath, Lipsa Jha, and the Technology Advantage Practice of The Boston Consulting Group, “Designing Digital Organizations—Summary of Survey Findings,” MIT Sloan CISR Working Paper No. 415, forthcoming.[/foot]

Despite the apparent importance of digital services platforms in an increasingly digital economy, our research found that only 5% of established companies have one. But that doesn’t mean companies aren’t building digital services: 26% of companies in our research have built APIs linking digital services to their master data and transaction processing systems. This suggests that companies are building services in a one-off fashion to address particular business needs. Past research suggests that building IT capabilities this way is risky.[foot]For a discussion of the risks of building systems without underlying architectural principles, see J.W. Ross, P. Weill, and D.C. Robertson, Enterprise Architecture as Strategy: Creating a Foundation for Business Execution, Harvard Business Review Press, 2006.[/foot] So how does a company build a digital services platform?

ARCHITECTING AND GOVERNING A DIGITAL SERVICES PLATFORM

In our earlier work, we observed that the architecture of a digital services platform is very different from the architecture of an operational backbone.[foot]Ross et al., “Designing Digital Organizations.”[/foot] In designing an operational backbone, architects establish a “target state” that highlights key inputs and outputs and how data flows among them.

The digital services platform, in contrast, does not have a target state. It is an organically growing set of components that constantly introduces new functionality; we think of it resembling a coral reef.

But that doesn’t mean that a digital services platform can’t— or shouldn’t—be architected. To better understand how companies go about building a digital services platform, we studied current governance practices related to developer platforms.[foot]Christian Umbach, “Management and Governance of External Developer Platforms—Examples at Akamai, Inc. and Uber Technologies, Inc.” (master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2017).[/foot] A developer platform exposes APIs to developers so they can use existing services and data to build new digital services. In addition to APIs, developer platforms often include tools to help developers quickly write new code compatible with existing services.

A developer platform exposes APIs to developers so they can use existing services and data to build new digital services. In addition to APIs, developer platforms often include tools to help developers quickly write new code compatible with existing services. A developer platform can support just internal developers or also expose services to external parties. External developer platforms (such as https://dev.twitter.com/) allow external developers to build functionality and linkages to benefit themselves and the host company.

Without well-designed governance, your digital services could become as unmanaged and unmanageable as the legacy systems of old.

Developer platforms are usually just one part of a company’s digital services platform. For example, many digital services platforms will include services for accessing, storing, and analyzing social media and sensor data. Despite its narrower scope, developer platforms have governance demands similar to digital services platforms. In particular, governance should help a company maximize benefits and minimize risks.

The benefits of developer platforms: A developer platform facilitates rapid development of new services by providing a base to build on. Internal and external developers can enhance or extend a company’s offerings, thereby attracting new customers or encouraging additional sales to existing customers. Companies should also realize efficiency benefits from the reuse of business and technology components. In addition, an external developer platform can help create a community of customers and/or partners.

The risks of developer platforms: Along with new revenues and efficiencies, a developer platform introduces new risks. For example, new services and APIs may proliferate and, if not well managed, lead to non-value-adding redundancy or obsolescence. External developer platforms may lead to unintended and undesired uses by partners. And of course, companies will be concerned about the security and privacy risks associated with managing access to data.

Akamai and Uber have introduced some governance practices, described below, that appear to maximize benefits and minimize risks of developer platforms.[foot]Ibid.[/foot]

Governance of the Developer Platform at Akamai

Akamai Technologies’ 6100+ employees make “the internet fast, reliable, and secure”[foot]“About Akamai,” Akamai Technologies, Inc.[/foot] for enterprise customers. The $2.3 billion company delivers nearly three trillion internet interactions every day.

Akamai has built out 150 discrete API-enabled services. The majority of these services are restricted to internal developers, but the company has created some APIs for limited use by existing customers. More recently, the company has been preparing to offer developer accounts that would enable customers to add their own functionality to Akamai products. Over time, Akamai would like to make more APIs available externally and expects to offer API access specifically to smaller companies that are currently not customers.

Many of Akamai’s existing API-enabled services were built within Chief Information Officer Kumud Kalia’s IT organization to support traditional IT services like billing. To build its external developer platform, Akamai created an Open Platform and Product Experience group under Vice President Corey Scobie within the product development organization. The group’s goal is to enable both internal and external developers to build functionality that gives customers greater visibility into, and control over, their use of Akamai technology. Still in early stages, the platform offers products such as APIs, SDKs (software development kits), and code libraries.

To address architectural issues related to the proliferation of API-enabled services, Akamai created an API working group. The group provides standards, conventions, and guidelines for all engineers who develop or use APIs. Architectural reviews help to align the development of APIs with existing systems and capabilities. APIs are catalogued and most are accessible on the company’s internal developer platform.

Akamai has appointed a governance team to oversee its developer platform. Called the Core Interlock Group, this team establishes priorities for development of services and APIs. The Core Interlock Group works across the company’s functions to identify business needs and establish priorities. Priorities are then approved at the executive level, and the Core Interlock Group assigns human and monetary resources. Cross-functional teams apply agile methodologies to incrementally build new tools and services.

The Core Interlock Group also has responsibility for managing external access to Akamai’s services. Until recently Akamai managed risk mostly by limiting access. Existing APIs were developed for specific customer needs. The company granted access on a need-to-know basis and allowable uses were specified in extensions to customer contracts.

Governance of the Developer Platform at Uber[foot]Umbach, “Management and Governance of External Developer Platforms.”[/foot]

Uber is a company that provides on-demand transportation solutions. Created in 2009, the company serves customers in 550 cities in 70 countries.

In 2014, Uber launched its developer platform and assigned a team to oversee its development. The team of more than two dozen people aims to empower developers—particularly external developers—to build moving experiences.

The Developer Platform team, headed by product and engineering leads, incorporates teams from Developer Relations, the API Platform, and API Features and partner engineers. The platform provides APIs, SDKs, and integration elements such as buttons and widgets. Its impact is to increase Uber’s reach—and its ridership, drivership, and deliveries.

The Developer Platform team establishes priorities for development of functionality. Internally, team members identify needs by working with business development teams. Externally, partner engineers generate ideas for new functionality from forums (such as Stack Overflow), events, hackathons, and from talking with external engineers. They target large industry players (e.g., Hyatt, United Airlines, StubHub, Amazon Alexa) as well as long tail developers who are building applications for niche markets. Uber also uses social media to ensure alignment between platform offerings and partners’ interests.

The API Features engineers work with partner engineers to define product roadmaps and then build new product components for the developer platform. The feature engineers have full lifecycle responsibility—initial design, feedback on technical proposals, and implementation and launch—for a product and its associated features. They apply agile development methodologies and ship code daily. The API platform team then scales and supports new features to ensure uptime and performance.

Governance at Uber is focused on generating opportunities, but the company has taken actions to limit inappropriate use by external developers. Accordingly, Uber gives business users full control over data generated by their components. Sales and business development teams negotiate contracts that support Uber’s partnerships with large brands. Upon accessing Uber’s functionality, all other external developers commit to terms of use the company has specified. Uber closely monitors use by third parties and can implement a “kill switch” if it perceives a partner is misusing an Uber service.

START DESIGNING GOVERNANCE FOR YOUR DIGITAL SERVICES PLATFORM

As the number of APIs in your company grows, your digital services could become as unmanaged and unmanageable as the legacy systems of old. We suggest that you:

- Articulate your digital business strategy to clarify your priorities for development of digital services.

- Create a team to define conventions and standards for building, cataloguing, evangelizing, pricing, and assessing your APIs and the digital services they link.

- For each digital service, assign an owner and enlist a cross-functional team to help define the roadmap for adding functionality and assessing the value of new features.

- Define and implement mechanisms for ensuring that your digital services—especially those accessible to external parties—are not abused.

Figure 1

Source: The Designing Digital Organizations 2016 Survey, N=171,

conducted jointly by the MIT Sloan Center for Information Systems

Research (CISR) and The Boston Consulting Group (BCG).

About the Authors

© 2017 MIT Sloan Center for Information Systems Research, Umbach and Ross. MIT CISR Research Briefings are published monthly to update the center's patrons and sponsors on current research projects.

MIT CENTER FOR INFORMATION SYSTEMS RESEARCH (CISR)

Founded in 1974 and grounded in MIT's tradition of combining academic knowledge and practical purpose, MIT CISR helps executives meet the challenge of leading increasingly digital and data-driven organizations. We work directly with digital leaders, executives, and boards to develop our insights. Our consortium forms a global community that comprises more than seventy-five organizations.

MIT CISR Associate Members

MIT CISR wishes to thank all of our associate members for their support and contributions.